Category Archives: Uncategorized

Theatre Street – by Peter Grant

Theatre Street

HOLLYWOOD has always excelled in those acid films that eat away at least something of the glamour of institutions which at other times they have asked us to admire – American politics, Big Business, even Hollywood itself. This last was recently taken apart in the Gloria Swanson film, Sunset Boulevard; and now, with All About Eve (script and direction: Joseph Mankiewicz), a similar dismantling takes place among the emotions, ambitions and vanities of that suffocating little alley – Theatre Street. And this film is not, as one might have thought, about a wide-eyed young actress desperately struggling to the top through the hazards of recurring amorous crises and leering producers; but about a brilliant though ageing star of the theatre, Margo Channing, who realizing for the first time what life will be like after the glory has departed, is beginning to lose her self-confidence. Into her life comes Eve, a lovely stage-struck young girl, with, so it seems, a tragic past; and Margo, to help her, employs her as a secretary. But Eve becomes rather more a reflection than a secretary … and to tell you more might spoil the film.

Admittedly it is hard to believe this story, which I must keep from you, but it’s nevertheless interesting and gripping; and the clever dialogue reflects plenty about life in the cut-throat circles of this vain, tight little theatre world. We meet Addison De Witt, an unpleasant but fascinating dramatic critic, clever enough even to scotch the plans of the villain of the piece – an unscrupulous actress whom Margo advises to put her Sarah Siddons awards where her heart should be. George Sanders – always happiest at his most offensive – plays this offensive fellow, who has neither award nor heart, to the life. And there’s Margo herself, witty, jagged, bitter, but as least generous and grown-up. This part is especially convincing because Bette Davis – a compelling and dazzling actress herself – plays it perfectly. Anne Baxter is just right for Eve, and I liked Gary Merrill as Bill, the theatrical producer. The film is considerably more talkie than movie but because the talkie is so good I’ll overlook the lack of movie.

That the part of Eve is as unbelievable as the story detracted little from my enjoyment of All About Eve; though without the character of Margo it would have been altogether too much of an orgy of malice. It is Margo – and Bette Davis, of course – who gives it proportion. And if it doesn’t give us anything like the last word on Theatre Street we certainly have a striking view of the vanity, ambition run to seed, brilliance and even humanity that one often finds in these highly competitive circles. You must leave your children at home and see the film from the beginning, and if anyone tries to tell you the story beforehand, don’t listen.

We know well enough by now that the human characters in Disney’s fairy-story cartoons don’t come to life in the brilliant way of the animals; but I think we should make allowances for them, as an experiment. In his new Cinderella, though the Prince is lifeless, Cinderella herself seems to be an advance on Snow White; though no-one would pretend that the animals haven’t the best of it, especially Cinderella’s friends, the mice, who call her most engagingly, “Cinderelly”. There’s less music than usual in this cartoon; but as it would, undoubtedly have sprung from modern dance music, which doesn’t match Disney’s work, I wasn’t sorry. The prettiest scene, when the colour’s at its best, is Cinderella’s drive in her pumpkin coach to the Ball. The film is obviously ideal for all children and most grown-ups.

There is a superficial resemblance between Crisis (Director: Richard Brooks) and the recent State Secret, for both films show the predicament of a doctor forced to operate on a dictator. But while State Secret was a comedy-thriller, Crisis is serious. The plum of the film is the portrait, by Jose Ferrer, of the dictator – excitable, handsome, cynical, greedy for power. And the direction is good, particularly in the crowd scenes, and in atmosphere. For example, the closeness to death of the dictator – from his political enemies without, from his brain tumour within – was extraordinarily well brought out. The film dwells too long on operating theatre procedure, but one must admit that the point – the dictator’s very natural fear of the knife getting the better of his conception of himself as a superman – is equally well made.

Crisis lasts long enough for us to witness the threatened revolution, and leaves us with the easy message that this will establish a tyranny just as bad as the other. Nevertheless, the power of the central situation is undeniable, and Crisis is well worth seeing. But don’t go if you only want pleasant entertainment.

PETER GRANT

This article was first published in March 1951 for the Federation of the Women’s Institute magazine “Home & Country”, Home Counties Edition, Volume 33, Number 3, and priced threepence.

Peter’s piece appears on page 77.

Filed under Uncategorized

Whitsuntide Cakes and Ale – by Peter Grant

Whitsuntide Cakes and Ale

In Mr. Blandings Builds his Dream House, Mr. Blandings (Cary Grant), a business man who buys a country place instead of making do with his New York home, is easy prey for the twisters of the countryside. They turn to their own account his romantic feelings about what he unblushingly calls his dream house; and Mrs. Blandings (Myrna Loy) – full of charm, sympathy and costly ideas – unwittingly helps them. Melvyn Douglas as Bill, their lawyer friend, foretells disaster everywhere, though unluckily, his advice is either given too late or never taken; and for every dollar Blandings intends to spend, ten slip down the drain. His story is futile, but often very funny.

It begins with Melvyn Douglas describing in the style of a news reporter the marvels of city life, the ease of travel there, and New York’s startling varieties of weather – which is all good satire. However, in showing us the Blandings home life in New York, the director (H.C. Potter) becomes heavy-handed and relies on outworn and tiresome slapstick; but once the Blandings fall among the wolves of the countryside, all is well – for us. First, a real estate man, accurately sizing them up, sells them a pup, a ramshackle building of which each of Mr. Blandings’ many surveyors – hired after the deal – says immediately and without further comment: “Tear it down.” Even the workmen see them as gullible cranks. One comic old man drills about two hundred feet down for water, at several dollars a foot; while only a few yards off, another blasts away some rock and floods the whole site. These workmen are never surprised; but the Blandings are shocked, and continue being shocked unto the very end.

Because it is sometimes heavy and slow, and above all has a cosy finish, Mr. Blandings misses being that rare product – a genuine film satire, with a bulldog bite. Satire is a mental purge, whose nature is too offensive for the men who finance films. The wish for big profits prevents their offending anyone. The script-writer of Mr. Blandings, however, and behind him the author of the original novel, have few fears of this kind and tread on a large number of American toes, laying waste most of the popular ideas about country dream houses. Sad that the end hasn’t the courage of the beginning.

Robert Montgomery in June Bride is a reporter on a glossy magazine, edited by Bette Davis, whom years before he had jilted. The story, into which is interwoven their bickering love affair, concerns a trip by the entire magazine staff to report an Indiana wedding. But “report” is perhaps the wrong word; for the Brinker family, whose daughter’s wedding it is, have to fit as nearly as possible the picture the readers of Miss Davis’s magazine have of them; so their home is rebuilt, their knick-knacks hidden, and perhaps a stone or two of weight teased from the waist-line of Mrs. Binker. And then the bride-to-be elopes with a former flame! Even “Home Life” – they really call it that – seems floored; but everything ends well. A good deal of somewhat mean joking arises from the impact of cynical New Yorkers on the Brinkers, and there is unhappily some sickly sentiment. But at its best the film is slick and funny.

In The Window, Tommy, an ordinary small boy, invents such vivid and untruthful stories that when, by chance, on a stifling summer night, he witnesses a murder, no one believes his account of it. His mother even tries to make him apologize to the murderers, a Mr. And Mrs. Kellerson. However, when Tommy has to spend the night alone in the tenement, the Kellersons decide to rid themselves of him; but after an exciting chase across roofs and through a disused rotting warehouse, Tommy outwits them and proves that for once he really has been telling the truth.

Natural is the word for all these characters, especially for Tommy (Bobby Driscoll). His parents (Barbara Hale and Arthur Kennedy) are really like ordinary parents; and the Kellersons are sinister without exaggeration. Especially good is Mr. Kellerson’s mixture of cruelty and interest when, on the night Tommy is alone, he traps him into opening his bedroom door. Ted Tetzlaff’s direction (most of it on the spot, on location as film people day) is sensitive, and there are unusual shots: one of Tommy and a policeman peering at one another across a huge desk; another of the flapping clothes which entice Tommy up to the Kellerson’s balcony to catch the night breeze, and incidentally to see the murder; and lastly to the murder itself, which seen through a slit in a blind becomes a mere flurry of shadows and legs. This excellent little work is Tetzlaff’s second film. I look forward to his third.

It seems to me that much of Emlyn Williams’ The Last Days of Dolwyn has the real voice of Wales. And this despite an unreal plot, and some studio scenery which looks absurd against genuine shots of the Welsh countryside. However, what really matters here is the impact on a small community of a plan to turn their valley into a reservoir and move them to a suburb, in Liverpool! Community – that’s the subject – and for the most part the villagers ring wholly true. Dame Edith Evans is splendid as the elderly slow-tongued widow, Merri, numbed by the idea of leaving her valley. Emlyn Williams as Rob, the boy who returns to get his own back on the village which scorned him as a child, is excellent – until melodrama spoils the part. Do see this film. The best of it is as fresh as spring water.

PETER GRANT

This article was first published in June 1949 for the Federation of the Women’s Institute magazine “Home & Country”, Home Counties Edition, Volume 31, Number 6, and priced threepence.

Peter’s piece appears on page 120.

Filed under Uncategorized

The Corporate Art – by Peter Grant

THE CORPORATE ART

In The Passionate Friends, Mary loves Steven, a biologist; but feeling that possessive romantic love will hinder her development she marries banker Howard Justin, who has similar ideas. The action of the film springs from the two opposing needs of Mary’s nature; and in veering between them she almost wrecks marriage and life. The original Wells novel, which probed ideas about “free love”, has shrunk in the censorship into this somewhat trite story. The hair-trigger emotions of these elegant characters argue a leisure which can hardly be imagined today, and to me at least make the film unreal, like some anaemic rose whose petals would scatter at the first breath of fresh air. For this one cannot blame the script writer (Eric Amber), whose work seems excellent; though after congratulating the producer (Ronald Neame) for assembling so brilliant a group, one must censure him, I think, for not finding them a worthy story. But should one criticize something for not being something else?

Yes, I think so, especially when as now the interpretative artists far outclass the work interpreted; since from this dilemma comes a clash between style and content. The director here (David Lean) resembles a pianist denied the important music of the day, and that so great a director should idle in a backwater off the main tide of great cinema is infuriating. Forty years of cinema have taught us that it is the supreme art of the actual, at its best when interpreting the world we live in. Hence I think it wasteful if one of our best cinema teams has to film hothouse stories like this. Yet how brilliantly they have done it! So far as I could see there is only one real flaw – in the early flashbacks. These obviously exist to shape the film and keep the preliminary dramatic situation from straggling; but once at least it was difficult to elucidate the chronology.

The most memorable scene for me was that in which the banker discovers without arousing suspicion, an intrigue between his wife and Steven; and looking astonishingly like Somerset Maugham he plays with them, cat-like, but with appropriate, self-possessed and icy disapproval. The scene is first-rate example of film drama without music. At the beginning Mary had innocently started the gramophone, some dance music wholly opposed to the mood into which the scene was drifting, and more important, to the expectant mood of the audience. But once she realizes the trap, even though the quarrel has begun, Mary walks deliberately to the gramophone and switches it off; and the climax of the quarrel, exploding in the husband’s unexpectedly passionate outburst, makes the full impact without rhetorical stimulus. In fact it dissatisfies us with the obvious musical rhetoric underlining Steven’s distracted and hurried departure. The scene itself, though, is perfect.

The main criticism apart, The Passionate Friends will delight any admirer of exciting film making; and no one should miss it because of the commonplace story. To begin with, though, every shot is to Lean what any individual style is to its author, one is always aware of true cinema, the corporate art; of, for example, Geoffrey Foot’s smooth editing and Guy Green’s expressive lighting and photography. John Bryan’s sets, though limited in scope, are good; and Richard Addinsell produces the necessary romantic evocative score for emotional seasoning, which in general is sensibly applied. But the really discriminate use of music has never been characteristic of Lean’s group. Claude Rains as the banker is superb, and Ann Todd and Trevor Howard could hardly be bettered. To see this movie with dialogue is to wash from your mouth the taste of all the talkies with movement you have ever seen. But David Lean is still awaiting his Beethoven.

Cry of the City (director, Robert Siodmak) is a fast, exciting and presumably authentic near-documentary, in the category of The Naked City and The Kiss of Death, which tells of the escape from jail and the final bringing to justice of a loveless cop-killing crook (Richard Conte). The scene of the man hunt, grey back streets, has desolate nostalgic yet impressive horror – which the characters share. The minor ones are especially good, and in one sense all the characters are minor. Even the principal cop (Victor Mature) isn’t a star. I can still see Marty, the outcast killer, stabbing to death a crooked lawyer, and a sequence concerning a blowsy masseuse with bulging calves, a prodigious appetite and the instincts of a shark. Yet there’s a Dickensian vitality about her, as there is about much of the film, despite its melodrama and clichés. Its roots are certainly where they should be, in humanity, and you couldn’t blow this story away with a breath of fresh air.

PETER GRANT

This article was first published in March 1949 for the Federation of the Women’s Institute magazine “Home & Country”, Home Counties Edition, Volume 31, Number 3, and priced threepence.

Peter’s piece appears on page 49.

Filed under Uncategorized

The Film Story – by Peter Grant

THE FILM STORY

THOUGH Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger are among our best directors, they never make completely fascinating films. For example, both Colonel Blimp and A Matter of Life and Death carried unsound stories – the first at odds with the characters, the second with an otherwise exciting fantasy. Often, of course, we overlook the ready-made stories of ordinary quota films; but that good plots are hard to find shouldn’t excuse two first-rate directors falling back on synthetic substitutes – one of the surest roads to filmic ruin. In their new work The Red Shoes Powell and Pressburger have offended especially badly in this way, and despite much splendid direction we feel delighted and annoyed by turns.

In this film Vicky Page becomes the prima ballerina of the famous Lermontov Company, making her name in a ballet based on a diluted version of Hans Anderson’s story The Red Shoes, wherein, as punishment for going to church in some red shoes, a little girl is bewitched to dance until an executioner cuts off her feet. And even then the shoes, with the feet still inside them, continue dancing: the punishment, one gathers, for vanity before God. For Vicky, however, the red shoes symbolise the life dedicated to ballet, the Lermontov Ballet, whose fanatical impresario intends to make her the greatest dancer alive. But when she rashly marries Julian Craster, the composer of the company, the ruthless Lermontov forces her to choose between husband and art; and here intrude the sinister implications of the fairy story, for incredibly, and I think absurdly, the red shoes dance Vicky to her end.

Within separate categories the directors undoubtedly succeed, often brilliantly, but in trying to combine a sentimental magazine story with near-documentary scenes (the ballet from back-stage), and a photographed stage ballet with one not far removed from a Disney Silly Symphony, they have made a hybrid. But even a hybrid by Powell and Pressburger isn’t dull. They begin, in fact, brilliantly – with eager balletomanes storming the gallery seats. This is a perfect direction – in its way, an opening as good as those of Lean’s two Dickensian films. But they close in bathos with The Red Shoes ballet performed without Vicky – doubtless an echo of that performance, after Pavlova’s death, of The Swan, with the curtain raised on an empty stage. However, to introduce the performance, Anton Walbrook as Lermontov – though good in the earlier scenes – gruesomely overacts a speech, which even if in character should have been suppressed. How anyone who could film this Pagliacci rubbish could also film the Parisian bill-poster demonstrating ballet steps to his mate is something to wonder at! The ballet I thought enchanting, and if it lacked the intimate third dimension of stage performances, it gained all the drama* that close-ups reveal, and also a vastly extended world to dance media*. As the diabolic shoe-maker, Leonide Massine (Ljubov) steals the entire picture; Moira Shearer (Vicky), who dances splendidly, acts in a charming unselfconscious way; and Robert Helpmann (Boleslawky) is excellent as her partner. Marius Goring makes what he can of the pathetic composer, for whom Brian Easendale has written effective music. Nevertheless, the work is disappointing, and even the directors never seem to have been certain just what kind of a film they were shooting; but because of Massaine, the sure-footed direction and the ballet, it is worth seeing.

To make The Naked City authentic the late Mark Hellinger fused it to a partly documentary technique, shot it on location (New York), and if he couldn’t get actual detectives and criminals, at least used actors who looked the parts. Barry Fitzgerald as a Homicide Bureau detective is the only star name, and he of course is excellent.

With no help from the usual clairvoyant detective the film tells a simple murder story, the Lieutenant Muldoon with his men make a routine investigation, tracing a few insignificant clues through the labyrinth of the City. The search is fascinating and convincing, and the documentary method provides the authentic background. Sometimes, however, it gives strange perspectives, the strangest being the domestic life of one of the detectives. This is quite irrelevant, and indeed embarrassing; but it does add depth to the work. The Naked City, in fact, succeeds where, at a much higher level of entertainment, The Red Shoes fails; and it does so because the director, Jules Dassin, knows his subject, gets to grips with it, is economical, and employs a good editor. Not that I am advocating a general return to documentary technique; but I should like to see someone follow the principle, in feature films, that stories grow from characters, and not vice versa. And if Powell and Pressburger ever dare to disregard the box office and do this, then they will make a film worth queueing for.

PETER GRANT

This article was first published in September 1948 for the Federation of the Women’s Institute magazine “Home & Country”, Home Counties Edition, Volume 30, Number 9, and priced threepence.

Peter’s piece appears on page 157.

*the words drama and media , in the third paragraph, have been added in an attempt to guess what Peter may have written so as to keep the piece flowing for the reader. The original magazines have suffered water damage and it has become impossible to determine what was written here. The missing words though, are relatively short.

Filed under Uncategorized

Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809-1847) by Peter Grant

Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy

(1809-1847)

As with Handel, a century earlier, the English expropriated Mendelssohn from Germany. It was perhaps inevitable; for surely no-one whom Prince Albert had played to, who had heard the Queen sing “with charming feeling and expression”, and who had discussed with her the future Edward VII, could possibly remain a foreigner? Goethe, who knew Mendelssohn as a boy and as a young man, is reported to have hailed him as a David to his Saul; his nearer contemporaries thought him at least the equal of Bach and Handel; yet by the turn of the century even his most ignorant critic was speaking of him as an overrated confectioner of drawing-room trifles, and his young lady patrons were swept away by their far from romantic daughters – Ibsen and Shaw abetting. Naturally the opponents of what was smugly conservative and sentimental in Victorian England could hardly admit to enjoying the very source of its shallow stream of music. So, like Tennyson, whose vast success and subsequent eclipse were similar to his, and who incidentally was born in the same year, Mendelssohn paid heavily for his drawing-room fame, his faҫile pen and his almost unclouded life. Now, of course, the position is different; and since we are neither romantics fighting conservative tradition nor oppressed children opposing our fathers, we can afford to enjoy Mendelssohn for what he is, without fighting him for what he never intended to be.

After such early adulation it was small wonder that Mendelssohn’s hostile critics took him for a mediocre prig, and remarkable that they were wrong. Every trap was laid for him. Even a present-day cinema “genius” could hardly have a more imposing and treacherous background. His father, a respectable Jewish banker, associated with most of the artists and intellectuals of his day. The grandfather, Moses, after beginning life at the starvation level, finished as a literary critic and philosopher, the colleague of Lessing, and the man responsible for the 18th century Jewish renaissance. One of his daughters married the brother of Schlegel, the great Shakespearean translator, and they both wrote romantic novels, advocated “free love”, and for a time at least acted on their principles. So behind him Felix had commerce, intellect, art, and even licence; and when his parents became Christians, assuming the name Bartholdy, he was brought up a Lutheran.

Taught first by his mother, an accomplished pianist and linguist, Felix then went to Zelter, the conductor of the Berlin Singakademie, and to Moscheles, the great pianist. A prodigy, he had written 13 symphonies for strings by his fifteenth year. This facility of composition never left him, but in some ways it was a doubtful gift; for often his music came too freely for him to discriminate about it, and had he not been at root a great composer he might easily have degenerated into a brilliant Kapellmeister – a fate that anyhow he did not always escape. At twenty he visited London, conducting his C minor symphony with a bâton, and this was still enough of a novelty to astound the Londoners. Mendelssohn also played Beethoven’s Emperor concerto, heard then for the first time in England. He had already begun his life-long championship of the almost totally neglected Bach, whose present day popularity rests entirely on that initiative. At eighteen Mendelssohn had got from Zelter a manuscript of the St. Matthew Passion, bought cheaply, it is said, from the effects of a dead cheese merchant; and though opposed by his teacher, who evidently lacked the foresight of this twenty-year old genius, early in 1829 he had the work performed, and as a result published; and throughout his life he spread the new gospel of Bach, playing the organ and keyboard works whenever he could.

The first book of Songs Without Words appeared in 1832, but was not immediately successful; though finally it was these pretty pieces that crowned Mendelssohn king of drawing rooms and annoyed him by obscuring his more serious works. In 1843 he founded the Conservatory at Leipzig, soon to become the Mecca of all nineteenth-century music students. Here he wrote most of the Elijah, significantly enough first conceived during a visit to England in 1837. Nine years later Birmingham heard the first performance, with the composer conducting; since then not even the depths of the Mendelssohn slump have dislodged this work from British choral societies.

Through only thirty-eight at his death, in a romantic age Mendelssohn avoided excess in both his art and his music. Later generations thought him too good to be true; and only within the last twenty years or so have we learned to mistrust this verdict. Yet even now we err on the side of conservatism, and many of Mendelssohn’s good and interesting works – the Reformation symphony, for example – are unaccountably neglected.

Adapting Shaw we might say that once there were two composers called Mendelssohn, one who wrote sentimental “salon” music, which excellently served its intended purpose, and another who created the Scotch and Italian symphonies, the Hebrides overture, and many fine separate movements in the choral works, string quartettes and concertos. That this second Mendelssohn was rarely able to resist the influence of the first makes discrimination hard; but unless we are to be foolish and dismiss as unworthy both the seventeen-year-old composer of the Midsummer Night’s Dream overture and the young man of the Italian symphony and the violin concerto, then discrimination there must be. And, of course, discrimination there is; for if we no longer idolize Mendelssohn, at least we have no need to hate him, and it is not by chance that now, a hundred years after his death, many of his finest works are still part of every orchestra’s standard repertory. Perhaps Queen Victoria knew best after all.

PETER GRANT

This article was first published in November 1947 for the Federation of the Women’s Institute magazine “Home & Country”, Home Counties Edition, Volume 29, Number 11, and priced twopence.

Peter’s piece appears on page 192.

Filed under Uncategorized

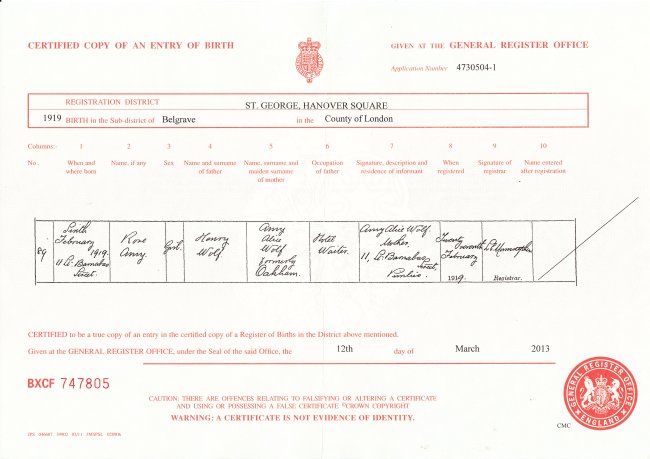

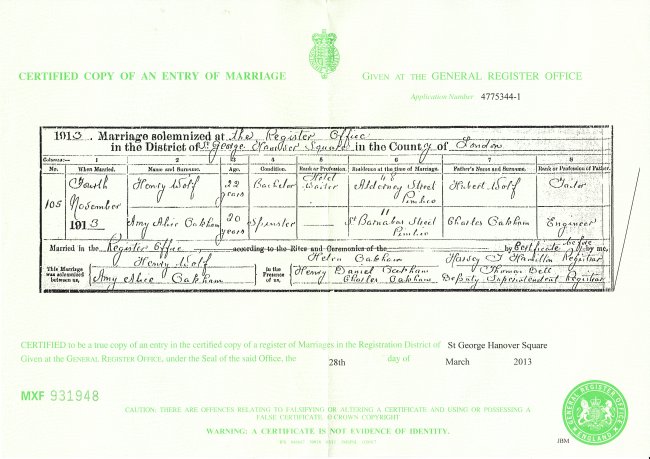

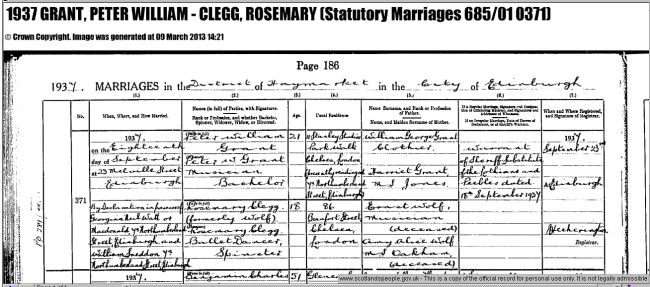

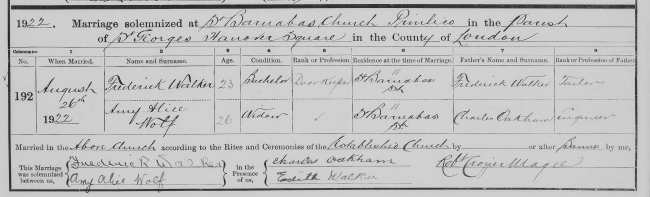

On the trail of a would-be concert pianist and writer: Peter Grant continued

Following my earlier blog about Peter Grant, I have continued delving and made a few more discoveries about him. I was contacted by the eminent musician and musical archivist who has done such an extraordinary amount of work to preserve the traditional music of the “London Irish” and traditional Irish Music generally: Reg Hall. You can ‘Google’ Reg and if you do so you will see he has featured on Irish television, TG4, the Gaelic speaking channel, from whom he has won awards for his extraordinary work in this field.

Anyway, Reg was able to confirm that the photographs my sister turned up of a young man in uniform were indeed of Peter Grant. They were also obviously taken at the back of the same house; 39 Lower Richmond Road, where he and my mother lived in Putney when they were married, and when my late half-sister Rosie “Reddy” was born.

My sister, my niece and I visited London in late August and took photos of the property. Unfortunately it was impossible to get around the back, but we could easily see the “L” shape of the building and the zinc roof of the shed (which obscured our entry). From the doorstep of their home, they would have had a wonderful view of the Thames, and a fine old pub “The Duke’s head” is just across the road; I think it is safe to say that this would have been their “local”.

Reg Hall also very kindly gave me a photo of Peter Grant in his later years, at the time he was married to Evelyn Honour Lucille Gilliat-Smith! This was when he was living at Barn Cottage in West Hoathley, West Sussex. I also learnt from Reg that Barn Cottage had been built by the Ursula Ridley. The Ridley’s were the “Lords of the Manor” in Hoathly and owned the whole village! Barn Cottage has changed now out of all recognition, but it was in their time a most interesting building, incorporating different architectural styles, the names of which I cannot draw to mind at present.

Peter’s house was crammed full of books and the shelves revealed he had more than a passing interest in psychiatry.

Peter’s grand-daughter, my niece, Louise, visited West Hoathly earlier this year and met two ladies who remember Peter. They very kindly gave her a collection of “Country Living” magazines featuring articles by Peter Grant; so at least one of his ambitions was materialised (He had wished to become a writer).

Peter’s War Records and his Death Certificate both say that he was a Paraplegic. Reg was able to elaborate on this injury sustained during the North African campaign; Peter received a bullet in the spine from a German aircraft.

I take solace from knowing that Peter, despite being a paraplegic, was somehow able to get about with the aid of a stick. I know (from Reg) that he spent years as an out-patient at the Stoke Mandeville Hospital; internationally recognised as a centre of excellence for spinal cord injuries.

I also know from Reg that Peter suffered permanent and agonising pain, but that he bore this with tremendous fortitude, always “keeping the bright side out” and remained cheerful and good-humoured nevertheless.

This morning I noticed from the Marriage Registry entry at the time he married my mother, that as well as giving his address at the time of 11 Stanley Studios, Park Walk, Chelsea, he also gave a “presently residing at” address of 7c Northumberland Street, Edinburgh. What I hadn’t noticed until today was that this is the same address as that of the two Witnesses; “Georgina Neal Watt or MacDonald” and “William Sneddon”. I hope that I can learn more about these two names, as they must have been known to Peter, surely, if he was residing with them. Perhaps they were relatives? Peter’s father came from Scotland (though he himself was born and brought up in Doncaster).

I shall continue to plough on until I have discovered all there is to know of Peter and I hope that in doing so he will not be forgotten.

I forgot to mention that before he was drafted into the army and sent off to become ‘canon fodder’ he had been studying at the Royal College of Music in London. He attended there for two years and was training to be a Concert Pianist. What folly it is to send men such as Peter; musical, literary characters, to fight as foot soldiers in a stupid, bloody war. Surely a gentle, sensitive man such as him should never be forced into such a position?

If you are reading this and have any information about Peter, however small or insignificant, I should be most grateful if you contacted me as every tiny scrap of information helps to build a clearer picture of this sweet, tragic figure.

Filed under Uncategorized

Hurricane Winds Bring Trees Down

Today the South West of Ireland experienced hurricane strength winds with gusts of 100mph.

I tweeted this:

When the storm had finally abated, we ventured out to see if any trees had been blown over. They had!

First was quite close by, at the corner of ‘The Pen’ and ‘Parc i dán’ where three trees and the ground under them were pulled up, bringing the sheep fence down and exposing the bottoms of the fence posts:

Next we went over to the ‘Cnocán’ (the field in front of the house where the two remaining pet lambs live) and at the bottom, two trees had toppled over, bringing up the sheep wire:

Just along from those two, a large tree was blown over into my neighbour’s field! Who gets to take a chainsaw to it under these circumstances?

In the same section of the field, following the drain/hedge along, west, a…

View original post 278 more words

Filed under Uncategorized